The Old Devil Saint Nick

The Spirit of Christmas in folklore...

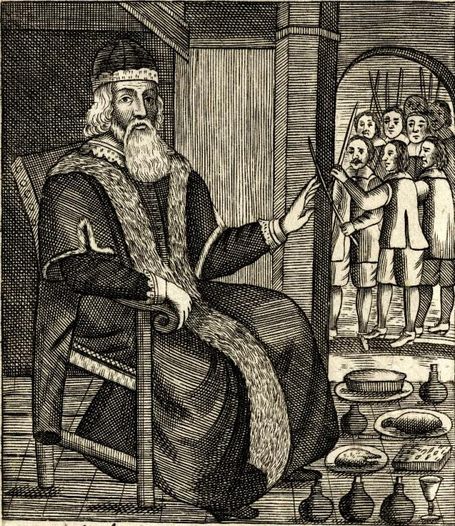

'Old Christmas', shown riding a yule goat. The original illustration is entitled 'Old Christmas' and is accompanied by a verse: "In furry pall yclad, / His brows enwreathed with holly never sere, / Old Christmas comes to close the wained year: Bampfylde". Robert Seymour (1798 – 1836) - "The Book of Christmas" by Thomas Kibble Hervey.

For the most part, history preserves the customs and conventions of the higher echelons of society, conserving the thoughts of the literate class. As any half decent student of history knows, the historical record is also heavily peppered with the ideas and biases of its author, in a similar way that current media reporting the same event today enjoys a vast gulf between the Liberal and Conservative view. The danger for our studies is when we identify a part of the record which supports our hypothesis and become blind to its own broader context. Such can be found in the writings, few as they are, upon ancient Druids or Teutons from predominantly Roman imperial and invading aristocrats [1]. This accounts for the paucity of academic credibility given to such sources in the historical record and given their proper context of place.

The beliefs, understandings and practices of the laypeople, or peasant class, are almost entirely unrepresented in literature and historical record. In this regard, conventions which constitute the traditions of the common class of society were amassed and transmitted in a predominantly oral manner, which provides us with some difficulty. The persistence of folkloric themes is one way in which we can hope to steal a glimpse of the fluid and adaptable habitus which informed the daily lives of our predecessors. Furthermore, it becomes a challenge to deduce meaning and understanding from the oral archeology of folktale, myth and custom. Nevertheless, there are tantalisingly small traces which, when taken in context, impart some window into the ideas which may have permeated society at its common level.

The popularity of such figures as Santa Claus in our present society has cemented the place of this rotund joy-giver in our own times as a customary and mythologised persona. The presence of the spirit of Christmas, known colloquially in various countries as Father Christmas, Santa Claus, Kris Kringle, Père Noël, and many others, has been retained with various associated origin myths which accompany this seasonal figure in every cultural group where he appears. Aside from the traditions associated with a collective peoples, there are sub-groups who have characterised their own mythology of Santa Claus with distinctive origins, used to explain their own idiosyncratic apprehension of the embodied spirit.

Most recently, neopagan and witchcraft sub-cultures have enjoyed the rise in popularity of the Krampus, the Central European folkloric counter figure to the benevolent Saint Nicholas, born of the underworld. More closely related is the Devil's sobriquet 'Old Nick', which is surprisingly similar to 'Old St. Nick'.

Literary records suggest that the term Old Nick for the devil is first reported in the mid 17th Century, however it is likely that the scholarly appearance in literature is preceded by colloquial use (in much the same way that words in our own parlance enter the dictionary today). The etymology of the term Nick for the Devil is obscure and there is no agreement or certainty as to its origin prior to the 1600s according to historical record. Attempted theories include the origin in Middle English "nycker, niker "water demon, water sprite, mermaid," from Old English nicor" (Source: Etymonline.com). Of course, in another meaning of "notch, groove or slit", it is perhaps easier to identify a similarity with another nickname for the Devil, Old Scratch.

The similarity in names aside, we find many scholars and academics positing a pre-Christian origin of Santa Claus in the medieval myth of the Wild Hunt. Of course, one of the main leaders of the Hunt in the Middle Ages was the Devil. Furthermore, medieval belief, as attested by apotropaic charms, indicates that the Devil was most feared to enter the home via the chimney. Indeed, such is the prevalence of concealed items within chimney breasts that we can readily identify it as being pertinent to the minds of medieval and early modern folk. By far the most common apotropaic find among the cache of spiritual middens is the common shoe, which is significant for a variety of reasons, one of which we shall discuss.

In the area of the Netherlands and Flanders lies the origins for much of our traditional Santa Claus customs. These crossed the Atlantic to the United States of America before returning to Europe through popular culture and arriving at the shores of Britain by the 1850s. Although Father Christmas was the embodiment of festive feasting and cheer (incorporating the Roman original as Lord of Misrule) from the Middle Ages, the Reformation saw him embattled and subsequently subdued upon the return to Christmas celebrations following the Restoration. In Medieval folk plays, Father Christmas represented the battle between the spirit and the flesh as envisaged through Christmas and Lent. However, the pious and joyless Protestants were not so favourable to the legacy of Father Christmas and, while not entirely vanishing, he remained a reduced spirit until Santa Claus arrived and the pair were conflated.

... we have to consider the spirit of the age, the typically medieval tendency to depict the fight with Satan, the struggle between good and evil, as dramatically and realistically as possible.

Saint Nicholas: A psychoanalytic study of his history and myth, Adriaan D. de Groot

The Santa Claus we now know, incorporating the older British Father Christmas and Lord of Misrule, presides over the period when order is upturned and merriment ensues. We can see some foundation in the Dutch Sinterklaas, who himself is derived from Saint Nicholas whose feast is marked on the 6th of December. Throughout Flanders and the Netherlands, children put out shoes by the chimney on the Eve of St Nicholas’ Day in anticipation of some gift or reward for good behaviour. This is a marked custom that bears some consideration in accord with the apotropaic shoes placed in chimneys to protect the incumbents from spiritual harm. Here we return to the significance of the chimney shoes charm.

In properly appraising the custom, we must consider the chimney principally in its liminal capacity as a tunnel which connects the earthy hearth with the heavenly sky above. Furthermore, the offerings of the flame are conveyed as spirit, breath, in the smoke as it rises upward. From the earliest holes in the ceilings of our ancestors’ primitive homes to the chimney pots of modern skylines, the vent which allows smoke to pass has been metaphorically associated with the heavens above and the nowl, or nail (Pole Star) about which the canvass of the night sky turns. In transporting messages from the earth to the heavens, what better method than the burnt offering which was so common to the ancients. The tradition is continued today in the letters that children pen to Santa Claus and consign to the flame with certainty that the missive will be safely delivered through the portal of the chimney and the magic of smoke to the Northern homeland of the seasonal spirit.

That our forebears might consider the opening to the sky as a potentially vulnerable entrance to the heart of the home is quite understandable in light of this. In performing operative magics to dissuade malevolent or disruptive spirits, therefore, is most certainly a folk custom which has survived in some way through various means today, from the sacrifice of burnt offerings to the letters to Father Christmas: whether as propitiatory offerings or discouraging charms. One thing that we can say with some confidence is that the hearth and chimney are ubiquitously a part of everyday life and, therefore, related folk customs which arrive with us must surely preserve some kernel of the traditions of our working class ancestors. Traditions that would have been beneath the pens of those for whom life afforded the privilege of education and the luxury of time and so went undocumented.

Of course, the traditions of sinterklaas which informed the later Americanised Santa Claus included a dark component who has been identified as the Devil himself:

...[the] answer is brief and admits of no doubt: Black Peter [Zwarte Piet] is the Devil!... 'Der Schwarze' (the Black One...) was a common designation for the Devil, which may help to explain why our Peter is black...

Saint Nicholas: A psychoanalytic study of his history and myth, Adriaan D. de Groot

Of course, there is no forgiving the racist origins in the depictions of Black Peter and the ill-informed appearances described as 'moorish' and obviously racially motivated. Black Peter does, nevertheless, contain within the folk custom some traces of our Old Nick, the Man in Black, Black Jack, for black was ever the Devil's colour in Medieval Europe as surely as his home is in the North. There has been some suggestion that the black is derived from the burnt offerings and the soot of the chimney, by which Peter appears. Unfortunately, the rather distasteful connotations that surround the use of 'blackface' in the context of this figure are too egregious and we shall leave it there.

In conclusion, there is such a myriad of traditions and time periods that inform our modern Santa Claus, of which one thing is certain: he is the seasonal embodiment of the spirit of merriment at the year's darkest period. During his seemingly Otherworldly celebrations, the world is turned upside down and he presides over the Misrule, order suspended as he moves and corresponds through the everyday chimney and hearth smoke, riding across the starry heavens in wild revelry as huntsman, upon the Yule Goat or with team of reindeer, adorned all in red furs and bidding us all to join in the joyfulness of the feast before Old Nick returns to his cold, Northerly home concealed from mundane activities for another year.

[1] For example, aside from one sentence from Julius Caesar, the historical record and archeology provides no evidence for the ‘wicker man’ in ancient times.